by Raha Iranian Feminist Collective

Originally posted on Jadaliyyah.

While building solidarity between activists in the U.S. and Iran can be a powerful way of supporting social justice movements in Iran, progressives and leftists who want to express solidarity with Iranians are challenged by a complicated geopolitical terrain. The U.S. government shrilly decries Iran’s nuclear power program and expands a long-standing sanctions regime on the one hand, and Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad makes inflammatory proclamations and harshly suppresses Iranian protesters and dissidents on the other. Solidarity activists are often caught between a rock and a hard place, and many choose what they believe are the “lesser evil” politics. In the case of Iran, this has meant aligning with a repressive state leader under the guise of “anti-imperialism” and “populism,” or supporting “targeted” sanctions.

As members of a feminist collective founded in part to support the massive post-election protests in Iran in 2009, while opposing all forms of US intervention, we take this opportunity to reflect on the meaning and practice of transnational solidarity between US-based activists and sections of Iranian society. In this article, we look at the remarkable situation in which both protests against and expressions of support for Ahmadinejad are articulated under the banner of support for the “Iranian people.” In particular, we examine the claims of critics of the Iranian regime who have advocated the use of “targeted sanctions” against human rights violators in the Iranian government as a method of solidarity. Despite their name, these sanctions trickle down to punish broader sections of the population. They also stand as a stunning example of American power and hypocrisy, since no country dare sanction the US for its illegal wars, torture practices and program of extrajudicial assassinations. We then assess the positions of some “anti-imperialist” activists who not only oppose war and sanctions on Iran but also defend Ahmadinejad as a populist president expressing the will of the majority of the Iranian people. In fact, Ahmadinejad’s aggressive neo-liberal economic policies represent a right-wing attack on living standards and on various social welfare provisions established after the revolution. And finally, we offer an alternative notion of and method for building international solidarity “from below,” one that offers a way out of “lesser evil” politics and turns the focus away from the state and onto those movement activists in the streets.

We hope the analysis that follows will provoke much needed discussion among a broad range of activists, journalists and scholars about how to rethink a practice of transnational solidarity that does not homogenize entire populations, cast struggling people outside the US as perpetual and helpless victims, or perpetuate unequal power relations between peoples and nations. Acts of solidarity that cross borders must be based on building relationships with activists in disparate locations, on an understanding of the different issues and conditions of struggle various movements face, and on exchanges of support among grassroots activists rather than governments, with each group committed to opposing oppression locally as well as globally.

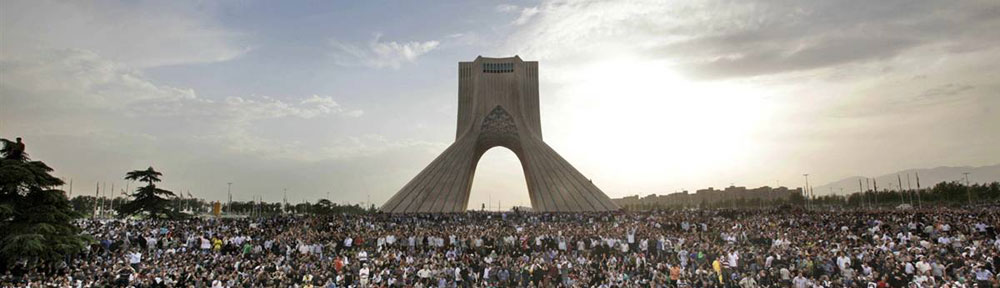

The spectrum of protest

Numerous protests and actions took place over the week of Ahmadinejad’s UN visit in September 2010, with at least eight activist groups organizing protests on the day of his General Assembly address–all claiming to speak in the interests of the Iranian people. However, despite some commonalities, these voices represented very different political approaches and agendas. Whether clearly articulated or not, one major fault line was on the question of the appropriate US and international role in relation to Iran, especially on the issues of sanctions and war.

The protests gaining the most media attention were organized by a newly-formed coalition called Iran180 and by the Mojahedin-e Khalq (PMOI). Both take a hard line, pro-sanctions position on Iran. Iran180, launched by the Jewish Community Relations Council of New York, organized a press conference under the banner “human rights, not nuclear rights.” The PMOI on the other hand, held a large rally of reportedly 2000 participants from far and wide. The PMOI is an organization known for its militant opposition to the Iranian regime and its anti-democratic, cult-like structure; it has been largely discredited among Iranians and is also listed as a “terrorist” organization by the State Department. Speakers included former mayor Rudy Giuliani, former US ambassador to the UN John Bolton, and British Tory MP David Amess, all calling for a hard line on Iran and apparently positioning the PMOI as the legitimate diasporic alternative to the current Iranian leadership.

By contrast, Where Is My Vote-NY (WIMV), an organization formed to express solidarity with Iranian protests after the contested election in 2009. They mobilized around a platform that called for holding Ahmadinejad accountable but also took an explicit no war and no sanctions position, making them the only organization to do so. WIMV’s strong anti-sanctions stance has been controversial among some human rights activists in the US who have supported sanctions that are supposed to target individual Iranian human rights violators. Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International pulled out of a WIMV-organized protest in September 2009 because they refused to endorse the WIMV platform. Below we size up the efficacy of “targeted” sanctions that claim to be in support of the human rights of Iranians.

The record of “targeted” sanctions

From 1990 until 2003, a United States-led United Nations coalition placed what amounted to crippling financial and trade sanctions on Iraq in an ostensible effort to weaken Saddam Hussein’s authoritarian regime. Sanctions, we were told, amounted to a humane way of combating intransigent authoritarianism around the world while avoiding mass bloodshed. The results of that strategy should have shattered these illusions for good. The complete collapse of the Iraqi economy during thirteen years of sanctions coupled with the inability of ordinary Iraqi people to access banned items necessary for their day-to-day survival–such as ambulances and generators–led to over half a million Iraqi civilian deaths. Furthermore, the sanctions were an utter failure in their purported primary goal—thwarting the Hussein regime while avoiding full-scale war. Not only was Hussein not dislodged by the sanctions, but he also managed to consolidate power throughout the ’90s while resorting to increasingly autocratic means of suppressing dissent. Finally, in March 2003, the United States and a small “coalition of the willing” began a full-scale military intervention in Iraq, which has shredded the fabric of Iraqi society and left a network of permanent US military bases–and Western oil companies–behind.

Despite the benefit of this hindsight, we are being told again to trust in the human rights agenda of a state-sponsored sanctions effort as an alternative to war, this time against the Islamic Republic of Iran. In fact, some form of sanctions against the Islamic Republic have been in place with little effect for over thirty years. But since President Barack Obama took office, the sanctions have been amped up to new heights. In June of 2010, a US-led United Nations coalition passed the fourth round of economic and trade sanctions against the Islamic Republic since 2006. The stated goal: limiting Iran’s nuclear program. Soon after, the European Union imposed its own set of economic sanctions. A month later, President Obama signed into law the most extensive sanctions regime Iran has ever seen with the Comprehensive Iran Sanctions Accountability and Divestment Act of 2010 (CISADA).

It should not be surprising, given the United States’ historic attempts at controlling Iranian oil, that CISADA’s primary target is the management of the Iranian petroleum industry. These sanctions would penalize any foreign company that sells refined petroleum products to Iran, which are a necessity for Iran’s primary industry as well as for the everyday functioning of modern life. This winter, shortages of imported refined gasoline forced the Iranian government to convert petro-chemical plants into makeshift refineries that produce fuel loaded with dangerous particles. As a result, the capital city of Tehran has been plagued by unprecedented levels of pollution, shutting down schools and businesses for days at a time and leading to skyrocketing rates of respiratory illnesses and at least 3,641 pollution-related deaths.

Further, Iran’s ability to import and export vital goods has been profoundly curtailed because the most powerful Western-based freight insurance companies—many of which worked with Iran until these most recent sanctions—can no longer do business with any company based in the Islamic Republic. Without insurance coverage, most international ports refuse any Iranian ships entry because they are not covered for potential damages. The current round of U.S.-led sanctions have had the effect of cutting off more of Iranian businesses because foreign companies are simply unsure of whether or not their business is sanctioned. As a stipulation of the US, EU, and UN sanctions, no corporations or private individuals can do business with the majority of Iranian banks or industries. Parts and supplies for a great deal of machinery—and not only those potentially associated with nuclear industry—are denied entry into Iran; indeed, one of the deadly examples of the effects of these sanctions in recent years has been the spate of commercial Iranian aircrafts that have crashed due to faulty or out-of-date parts. These measures have already had disastrous effects on the Iranian economy and the health ordinary Iranian citizens, adding to historic levels of inflation, unemployment and pollution-related illness.

Despite mounting evidence warning against the humanitarian disaster of unilateral, state-engineered sanctions, many people outside of Iran are still compelled to support them as a diplomatic alternative to war. The operating principle behind such a belief is that these sanctions—unlike those wielded against Iraq, which limited all facets of the economic life of the nation—only target certain individuals, groups, and aspects of economic life. In the case of the Islamic Republic, the argument goes, these individuals and groups are directly linked to the state, including the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC–or Sepah Pasdaran) and the paramilitary Basij forces, which do indeed command much of the economic resources of the Islamic Republic. Unfortunately, the reality of even “targeted” sanctions is not nearly so rosy. To see why this strategy is almost certain to be a failure, we consider the recent example of Zimbabwe.

Since 2001, there has been a similar set of so-called “smart” sanctions in place against Zimbabwe in an effort to weaken President Robert Mugabe and to force him to join a coalition government with his principal political opponents. In the decade after the imposition of these sanctions, Zimbabwe has suffered enormously, experiencing one of the most cataclysmic instances of hyperinflation in history, skyrocketing unemployment rates, a startling lack of basic necessities, a rapidly growing income disparity, and the rise of a black market for goods that only an elite few can access. Indeed, the story in Zimbabwe is remarkably similar to that in Iraq: in both cases the authoritarian state only increased its power as a result of the economic stranglehold on the country due to its monopoly over all of the available wealth and resources in the nation. As the Iraqi and Zimbabwe cases demonstrate, sanctions are not an effective means to avoid war, nor do they inevitably undermine repressive and authoritarian states. Most importantly of all, they further immiserate the very people they claim to be helping.

Often, these failed examples are countered by one historic success story, namely, the divestment and sanctions movement against apartheid South Africa–a very compelling instance of international solidarity with a mass domestic opposition movement. Is this an apt analogy for the Iranian case? A crucial difference is that sanctions against South Africa came only after a divestment campaign led by South African activists, which succeeded in convincing a great deal of private capital to flee the country before US or UN involvement. As a tactic developed and deployed within South Africa, sanctions were not the result of power machinations between antagonistic states or a strategy that enhanced US global dominance.

Iran presents a very different situation. No member of any Iran-based opposition group—from leaders of the “green” movement, to activists in the women’s and student movement, to labor organizers—have called for or supported the US/UN/EU sanctions against the Islamic Republic. On the contrary, leaders from virtually all of these groups have vocally opposed the implementation of sanctions precisely because they have witnessed the Iranian state grow stronger, and the wellbeing of ordinary Iranians suffer, as a result. Imposing sanctions in the name of “human rights,” as the US did for the first time this fall, doesn’t alter these outcomes. The US government’s long record of either complicity with or silence regarding the treatment of dissidents in Iran–from the 1950s when it helped train the brutal SAVAK torture squads right through to the post-election crackdown in 2009–makes it nothing if not hypocritical on the issue of human rights in Iran.

The spectrum of support

In stark contrast to the range of groups protesting the Iranian president and the Islamic Republic’s policies, some 130 activists from anti-war, labor and anti-racist organizations took an altogether different approach in September 2010, attending a dinner with Ahmadinejad hosted by the Iranian Mission to the UN. According to one attendee, the goal of the dinner was to “share our hopes for peace and justice with the Iranian people through their president and his wife.” During two and half hours of speeches, activists embraced Ahmadinejad as an ally and partner in the global struggle for peace and, with few exceptions, ignored the fact that his administration is responsible for a brutal crackdown on dissent in Iran (click here for one notable exception).

Rather than listening to the millions of Iranians who protested unfair elections and political repression, these activists heard only the siren song of Ahmadinejad’s “anti-imperialist” stance, his vehement criticism of Israel and his statements about US government complicity with the September 11th attacks. Their credibility as consistent supporters of social justice has been shipwrecked in the process. Many of these groups are numerically small organizations with histories of denying atrocities carried out by heads of state that oppose US domination.[1] But some attendees are national figures, such as former US Congresswoman and 2008 Green Party presidential candidate Cynthia McKinney, who has been a beacon of principled opposition to neo-liberalism and the “war on terror.” While it is important not to lump all of the groups and individuals together as sharing the same set of political ideologies or organizing strategies, we need to investigate the reasons that these activists showed up to express support for the current Iranian regime. Below we take up the most common reasons attendees expressed for standing with the regime–that it has populist economic policies benefiting workers and the poor, is anti-imperialist and pro-Palestine.

Do Ahmadinejad’s policies support Iranian workers and the poor?

One of the most bewildering misrepresentations of Ahmadinejad outside Iran has been around his economic policies, which are often represented by the US left as populist or even pro-working class. In reality, the extent and the speed of privatization in Iran under Ahmadinejad has been unprecedented, and disastrous, for the majority of the Iranian people. The International Monetary Fund (IMF)’s report on the Iranian state’s neo-liberal policies glows with approval, confirming once again that the Fund has no problem supporting undemocratic attacks on the living standards of ordinary people. Privatization in Iran has happened under government/military control. State-affiliated actors, mainly Sepah, have bought a huge share of the country’s economic institutions and contracts–from small companies all the way to the largest national corporations such as telecommunications, oil and gas. Recently, despite vast opposition even from the parliament, the government annulled gasoline and food subsidies that have been in place for decades. Gas prices quadruped, while the price of bread tripled, almost overnight. This is an attack on workers and the poor of historic proportions that had been in the works for many years but was delayed due to fear of a popular backlash. It was only under conditions of extreme militarization and suppression of dissent that Ahmadinejad’s administration could finally implement this plan. Arguing that subsidies should go only to those the regime decides are deserving, the government will now be able to use this massive budget to reward supporters and/or buy loyalty. The massive unregulated import of foreign products, especially from China, has made it impossible for agricultural and industrial domestic producers to survive. Import venues are mainly controlled by the government and Sepah, which profit enormously from their monopolies. These hasty and haphazard developments have severely destabilized Iran’s economy in the past few years, leading to rocketing inflation (25-30%) and growing poverty. Unemployment is very high; no official statistics are available but rough estimates are around 30%, creating fertile ground for recruitment into the state’s military and police apparatus (similar to the “poverty draft” in the United States).

Is the Ahmadinejad administration anti-imperialist?

The 1978–79 revolution was one of the most inspiring popular uprisings against imperialism and homegrown despotism the world has seen, successfully wresting Iran away from US control over Iranian oilfields and ending its role as a watchdog for US interests in the region. Denunciations of American imperialism were a unifying rallying cry and formed a key pillar of revolutionary ideology. However, in the more that thirty years since, the Iranian government has, like all nations, ruthlessly pursued its interests on the world stage. Despite its anti-American/anti-imperialist rhetoric, Iran cannot survive without capital investment from and trade with other “imperial” nations, without integration into a world market that is ordered according to the relative military and economic strength of various states. Witness the large oil, gas, and development contracts granted to Russia and China, and the way that these countries, as well as France and Germany, have cashed in on the Iranian consumer goods market. The Islamic government has even cut deals with the US, such as during the infamous Iran-Contra episode, when it served its interests. US opposition to Iran’s nuclear program, and multiple rounds of sanctions, should be understood as part of the American effort to re-exert control over this geo-politically strategic country and re-enter the race for Iranian energy resources and markets from which it has been shut out.

Iran’s foreign policy cannot and should not be reduced to one individual’s inflammatory speeches. In fact, the same Ahmadinejad who grabs western media headlines by criticizing the US is the first Iranian president to send a letter directly to a US president requesting a new era of diplomacy, something unthinkable under previous administrations. Diplomacy, to be clear, carries with it the goal of re-entering a direct relationship with the so-called “Great Satan.” Far from acting as an outpost of anti-imperialism, the Ahmadinejad administration is maneuvering to cut the best deal possible and to renegotiation its place in the global hierarchy of nations. Given its massive oil and gas resources and strategic location, Iran would likely be playing a far more significant and powerful role if not for decades of isolation, sanctions and hostility from the US. It is in the Iranian governments interests to break this stranglehold. Its strategy is to play all cards possible in extending its regional influence in smaller and weaker countries, such as Lebanon and the occupied territories of Palestine. As Mohammad Khazaee, the Iranian ambassador to the UN told the New York Times, Iran is a regional “heavyweight” and deserves to be treated as such.

The Iranian government’s support for Palestinians also scores it major points with many leftists in the US and around the world. Again, it is crucial to see through the rhetoric and examine the more complex aims and effects of Iran’s policies. While the Iranian government does send material aid to Palestinians suffering under Israeli blockades and in refugee camps in Lebanon, they have also manipulated the situation quite cynically for purposes that have nothing to do with Palestinian liberation. Using money to buy support from Palestinians, and financing and arming the Hezbollah army in Lebanon, are crucial ways the Islamic Republic exerts its influence in the region.

There is no mechanism for Palestinians or Lebanese people, who are impacted by Iran’s actions, to have any say in how Iran intervenes in their struggles, even when the results are harmful. For instance, Ahmadinejad’s holocaust denials undermine the credibility of Palestinian efforts to oppose Israeli apartheid by reinforcing the false equation between anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism. At the 2001 UN conference against racism in Durban, South Africa, an anti-Zionist coalition emerged and got a hearing. But at the 2009 conference in Geneva, Ahmadinejad’s speech on the first day overshadowed the whole conference and undermined any possible critique of Israel, creating a serious set back for the anti-Zionist movement.

Relentless state propaganda about Palestine coming from an unpopular regime has tragically resulted in the Iranian people’s alienation from the Palestinian’s struggle for freedom. Leaving aside the hypocrisy of Ahmadinejad claiming to care about the rights of Palestinians while trampling on those of his own citizens, the policy of sending humanitarian aid to Palestinians while impoverishing Iranians has produced massive domestic resentment. In an article on The Electronic Intifada, Khashayar Safavi attempted to link the pro-democracy Iranian opposition to broader questions of justice in the region. “We are not traitors, nor pro-American, nor Zionist ‘agents,'” he wrote, responding to Ahmadinejad’s verbal attacks on the movement, “[W]e merely want the same freedom to live, to exist and to resist as we demand for the Palestinians and for the Lebanese.” Unfortunately, sections of the US left support the self-determination of Palestinians while undermining that of Iranians by supporting Ahmadinejad’s government. We now look at some of the key problems of Ahmadinejad’s government, exposing the high cost of aligning with repressive state leaders.

Harsh realities for labor and other social justice organizing in Iran

Currently no form of independent organizing, political or economic, is tolerated in Iran. Attempts at organizing workers and labor unions have been particularly subject to violent repression. The crushing of the bus drivers’ union, one of the rare attempts at independent unionizing in the last few decades, is one of the better-known examples. The story of Mansour Osanloo, one of the main organizers of the syndicate, illustrates the incredible pressure and cruelty labor organizers and their families experience at the hands of the regime. In June 2010, his pregnant daughter-in-law was attacked and beaten up by pro-regime thugs while getting on subway. They took her with them by force and after hours of torture, left her under a bridge in Tehran. She was in dire health and had a miscarriage. These unofficial security forcescontinued to harass her at home in order to put psychological pressure on Osanloo, who is still in prison and is not yielding to the government’s demands to stop organizing. Currently, even conservative judiciary officials are complaining about violations of their authority by parallel security and military forces who arrest people, conduct interrogations and carry out torture, pressure judges to issue harsh sentences, and are implicated in the suspicious murders of dissidents. (In the past few months, not only political dissidents, but even physicians who have witnessed some of the tortures or consequences of them, have been murdered.)

No opposition parties are allowed to function. No independent media–no newspapers magazines, radio or television stations–can survive, other than websites that must constantly battle government censorship. The prisons are full of journalists and activists from across Iranian society. Conditions in Iran’s prisons are gruesome. Prisoners are deprived of any rights or a fair trial, a violation of Iranian law. After the election protests, killing, murder and rape of protesters and prisoners caused a scandal, which resulted in the closing of the notorious Kahrizak prison. Executions continue, however, as the government has meted out hundreds of death sentences in the last year. Iran has the second highest number of executions among all countries and the highest number per capita. In January 2011, executions soared to a rate of one every eight hours.

The women’s movement has been another major target of repression in the past few years. Dozens of activists have been arrested and imprisoned for conducting peaceful campaigns for legal equality; many have been forced to flee the country and many more are continually harassed and threatened. Women collecting signatures on a petition demanding the right to divorce and to child custody are often unfairly accused of “disturbing public order,” “threatening national security,” and “insulting religious values.” Ahmadinejad’s government employs a wide range of patriarchal discourses and policies designed to roll back even small gains achieved by women.

Ahmadinejad’s anti-immigrant positions and policies are the harshest of any administration in the past few decades. The largest forced return of Afghan immigrants happened under his government, ripping families apart and forcing thousands across the border (with many deaths reported in winter due to severe cold). Marriage between Iranians and Afghan immigrants is not allowed and Afghan children do not have any rights, not even to attend school. Moreover, Ahmadinejad’s government has been repressive toward different ethnic groups in Iran, particularly Kurds. It is promoting a militarist Shia-Islamist-nationalist agenda and escalating Shia-Sunni divisions.

Given these realities, how is it that large parts of the US left can support Ahmadinejad? We now look at the confusions that make such a position possible.

US left support for Ahmadinejad

Despite the many differences between the individuals and groups represented at that dinner with Ahmadinejad a few months ago, what the overwhelming majority of them have in common is a mistaken idea of what it means to be anti-imperialist or anti-war. The sycophantic speeches at the dinner can be understood as an enactment of the old adage “the enemy of my enemy is my friend.” There are two problems with this approach. The first is that it equates governments with entire populations, the very mistake the activists at that dinner are always saying we shouldn’t make when it comes to US society. The second problem is that support for Ahmadinejad means siding with the regime that crushed a democratic people’s movement in Iran. This position pits US-based activists who want to stop a war with Iran against the democratic aspirations and struggles of millions of Iranians.

Part of the confusion may stem from a distorted notion of what it means to speak from inside “the belly of the beast.” In other words, the argument goes, those of us in the United States have a foremost responsibility to oppose the actual and threatened atrocities of our own government, not to sit in hypocritical judgment over other, lesser state powers. But in the case of the vicious crackdown on all forms of dissent inside Iran, not judging is, in practice, silent complicity. If anti-imperialism means the right to only criticize the US government, we end up with a politics that is, ironically, so US-centric as to undermine the possibility of international solidarity with people who have to simultaneously stand up to their own dictatorial governments and to the behemoth of US power. The fact that the US is the global superpower, and therefore the most dangerous nation-state, does not somehow nullify the oppressive actions of other governments. China, for example, is increasingly participating in economic imperialism across Asia and Africa, exploiting natural resources and labor forces well beyond its borders. There is more than one source of oppression, and even imperialism, in the world. The necessity to hold “our” government accountable in the US must not preclude a crucial imperative of solidarity–the ability to understand the context of other people’s struggles, to stand in their shoes.

If any of the activists defending Ahmadinejad would honestly attempt to do this, they might have some disturbing realizations. For example, if those same individuals or groups tried to speak out and organize in Iran for their current political agendas–against government targeting of activists, against ballooning military budgets, against media censorship, against the death penalty, against a rigged electoral system, for labors rights, women’s rights, the rights of sexual minorities and to free political prisoners–they would themselves be in jail or worse.

Given that these are the issues that guide the work of these leftists in the US, we must ask: don’t the Iranian people also deserve the right to fight for a progressive agenda of their choosing without execution, imprisonment and torture? As we demand rights for activists here, don’t we have to support those same rights for activists in Iran?

Solidarity: concrete and from below

In the tangle of conflicting messages about who speaks for the “people of Iran”–a diverse population with a range of views and interests–what has been sorely lacking in the US is a broad-based progressive/left position on Iran that supports democratization, judicial transparency, political rights, economic justice, social freedoms and self-determination.

There is no contradiction between opposing every instance of US meddling in Iran–and every other country–and supporting the popular, democratic struggles of ordinary Iranians against dictatorship. Effective international solidarity requires that the two go hand in hand, for example, by linking the struggles of political prisoners in Iran and with those of political prisoners in the US, not by counterposing them. Iranian dissidents, like dissidents in the US, see their own government as their main enemy. The fact that Iranian activists also have to deal with sanctions and threats of military action from the US only makes their work and their lives more difficult. The US and Iranian governments are, of course, not equal in their global reach, but both stand in the way of popular democracy and human liberation. US-based activists must not undermine the brave and endangered work of Iranian opposition groups by supporting the regime that is ruthlessly trying to crush them.

We are calling for a rethinking of what internationalism and international solidarity means from the vantage point of activists working in the US. Internationalism has to start from below, from the differently articulated aspirations of mass movements against state militarism, dictatorship, economic crisis, gender, sexual, religious, class and ethnic oppression, in Iran, in the US and all over the world. For activists in the US, this means being against sanctions on Iran, whether they are in the name of “human rights” or the nuclear issue. It means refusing to cast the US as the land of progress and freedom while Iran is demonized as backward and oppressive. Solidarity is not charity or pity; it flows from an understanding of mutual–though far from identical–struggle. It means consistent opposition to human rights violations in the US, to the rampant sexism and homophobia that lead to violence and destroy people’s lives right here. But we don’t have to hide another state’s brutality behind our complaints about conditions in America. We have to be just as clear in condemning state crimes against activists, journalists and others in Iran, just as critical of the Iranian versions of neo-liberalism and oligarchy, of attacks on trade unions, women and students, as we are of the US versions.

For solidarity to be effective, it must be concrete. US-based activists need to educate ourselves about Iran’s historic and contemporary social movements and, as much as possible, build relationships with those involved in various opposition groups and activities in Iran so that our support is thoughtful, appropriate to the context and, ideally, in response to specific requests initiated from within Iran. It is our hope that these struggles may be increasingly linked as social justice activists in the US and Iran find productive ways of working together, as well as in our different contexts and locations, towards the similar goals of greater democracy and human liberation.